Ecological Deficits

Today, more than 80 percent of the world’s population lives in countries that are running ecological deficits, using more resources than what their ecosystems can regenerate.

Resources. There it is again!

Degraded ecosystems take time to recover from overexploitation, while some might never bounce back even when exploitation stops.

Unfortunately, most countries struggle to guarantee the long-term use of natural resources at minimal environmental cost while guaranteeing social and economic development.

Over 7.8 billion people are living on the planet today.

In 1951, we were 2.5 billion.

Do the math.

Approximately 1.5 billion hectares (11%) of the world’s land surface is used for crop production. That’s about 36% of the total global land suitable for crop production.

While there are still 2.7 billion hectares more that could be used for agricultural purposes, overreliance on land resources for food production could lead to serious issues in the future.

Also, the use of heavy farming equipment and machinery and poor soil management practices also destroys the soil structure and makes it unsuitable for growing plants.

In a nutshell, all these elements combined plus others soon to be mentioned in future articles create what we call an “ecological footprint”.

According to the dictionary, Ecological Footprint stands for the impact of a person or community on the environment, expressed as the amount of land required to sustain their use of natural resources.

Basically, it is the only metric that measures how much nature we have and how much nature we use.

Ecological Footprint accounting measures the demand on and supply of nature.

On the demand side, it adds up all the productive areas for which a population, a person or a product competes. It measures the ecological assets that a given population or product requires to produce the natural resources it consumes and to absorb its waste, especially carbon emissions.

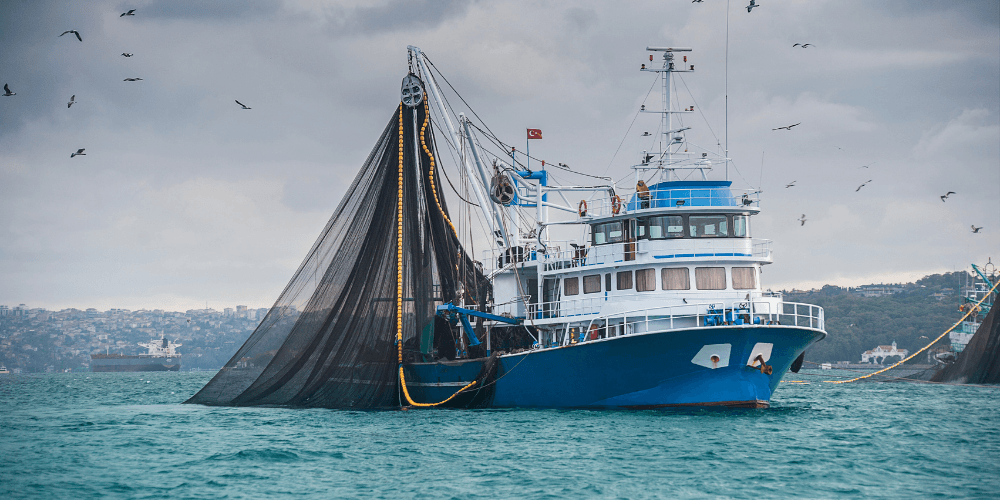

Also, it tracks the use of productive surface areas. Typically, these areas are: cropland, grazing land, fishing grounds, built-up land, forest area, and carbon demand on land.

On the supply side, a city, state or nation’s biocapacity represents the productivity of its ecological assets (including cropland, grazing land, forest land, fishing grounds, and built-up land). These areas, especially if left unharvested, can also serve to absorb the waste we generate, especially our carbon emissions from burning fossil fuel.

According to the Global Footprint Network, a population’s Ecological Footprint exceeds the region’s biocapacity, that region runs a biocapacity deficit. Its demand for the goods and services that its land and seas can provide—fruits and vegetables, meat, fish, wood, cotton for clothing, and carbon dioxide absorption—exceeds what the region’s ecosystems can regenerate. In more popular communications, we also call this “an ecological deficit.”

A region in ecological deficit meets demand by importing, liquidating its own ecological assets (such as overfishing), and/or emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

If a region’s biocapacity exceeds its Ecological Footprint, it has a biocapacity reserve.

Conceived in 1990 by Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees at the University of British Columbia, the the Ecological Footprint launched the broader Footprint Movement, including the carbon footprint, and is now widely used by scientists, businesses, governments, individuals, and institutions working to monitor ecological resource use and advance sustainable development.

Sustainable development is successful only when it improves people’s well-being without degrading the environment.

But a question remains: how willing are we go that extra mile to shift our modus operandi and ensure a considerable decrease on our footprint?

Think globally, act locally

Think globally, act locally

Leave a Reply